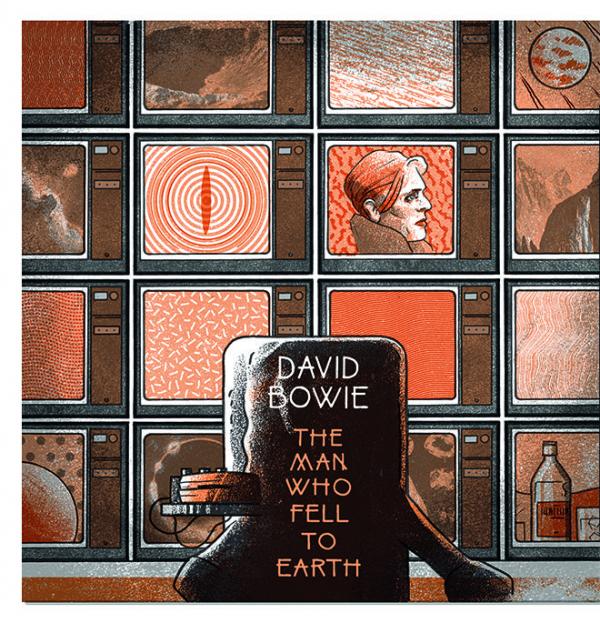

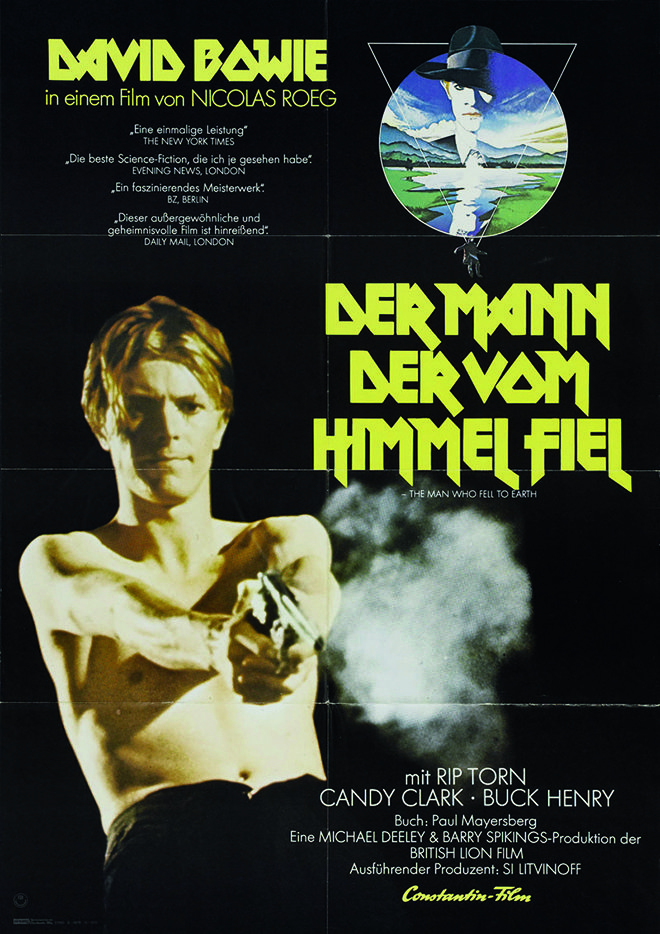

Missing Soundtracks: The Man Who Fell To Earth

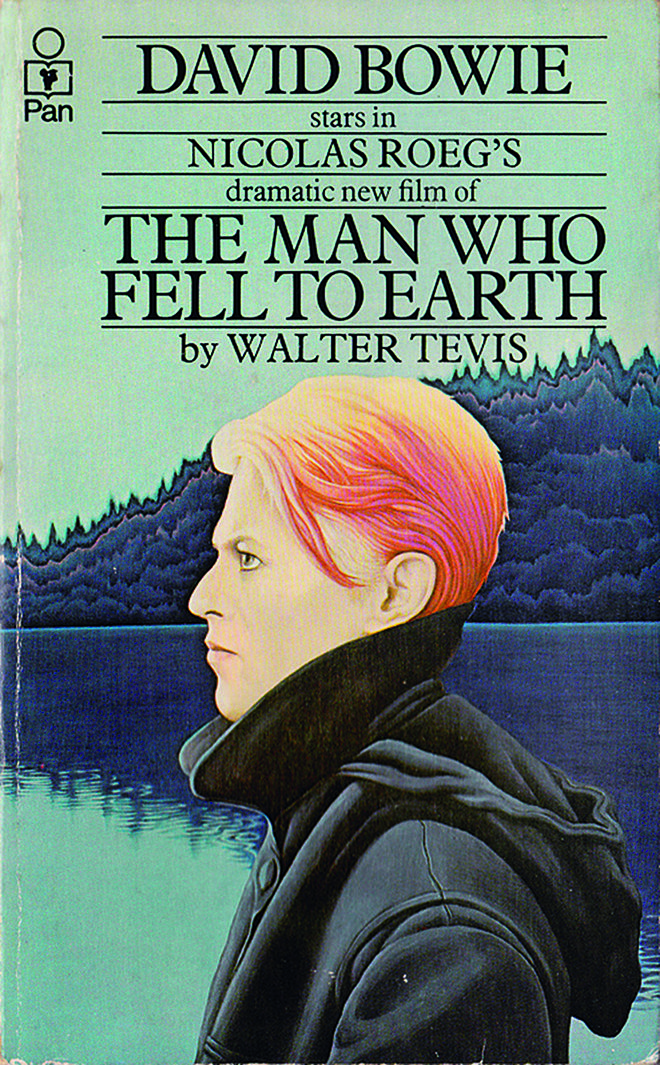

Flip over the 1976 Pan edition of Walter Tevis’ 1963 novel The Man Who Fell To Earth, re-released to tie in with the film of the same name by Nicolas Roeg that featured the Thin White Duke in his first major movie, and you’ll find the following tantalising statements: music by David Bowie; album available on RCA. After scratching your head and attempting to recall the cover of the release, and before you head to Discogs to fill that hole in your record collection, the disappointing news is that it doesn’t exist – not as a legitimate release, and certainly not as was originally intended.

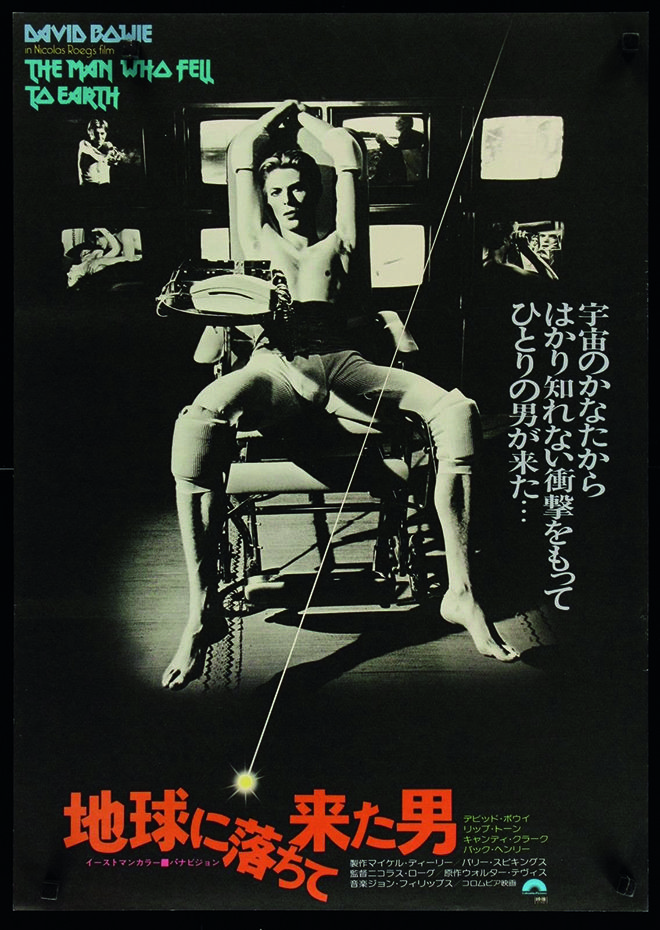

“The Man Who Fell To Earth is a powerful love story; a cosmic mystery; a spectacular fantasy; a shocking, mind-stretching experience in sight, in space, in sex,” runs the deep-throated voiceover to the movie’s trailer. The casting of David Bowie – billed as “phenomenon of our time” and riding his first peak of US popularity – in his debut major motion picture was big news. Roeg had seen the elegantly wasted musician profiled in 1975 BBC documentary Cracked Actor and considered him perfect for the role of Thomas Jerome Newton – a humanoid extra-terrestrial on a mission to bring life-giving water to his dying home planet – despite his lack of film experience. Shooting began in 1975, and it was widely assumed that Bowie would also write the score for the film – the star admitted as much on US TV show Soul Train in November that year. “I’m doing the soundtrack for The Man Who Fell To Earth with a friend of mine, Paul Buckmaster,” he revealed. Best known for his orchestral collaborations with Elton John, Buckmaster acted as arranger for Bowie on 1969’s breakthrough Space Oddity. According to excellent fan-site BowieGoldenYears, the original plan was that RCA would contribute to the movie and Bowie would provide a soundtrack to promote the film.

US rock magazine Creem already had the scoop in the bag when it conducted an interview with him on set. “That’ll be the next album – the soundtrack,” Bowie explained, which would have made The Man Who Fell To Earth the follow up to the plastic soul of Young Americans – the album which broke him in the States – and the precursor to the more experimental Station To Station. “I’m working on it now… doing some writing,” he added. “But we won’t record until all the shooting’s finished. I expect that the film should be released around March [1976], and we want the album out ahead of that, so I should say maybe January or February.”

Talking about his working methods, he added, presciently: “I just use music to achieve something I have in mind, an idea or a feeling I want to get across. But I’m not one of those people who treat it as something sacred. You’ve got to play around with it or it becomes a dreadful bore.” Music as idea… Music as feeling… both of these concepts are explored to devastating effect on Bowie’s 1977 Low LP, partially in collaboration with ambient music pioneer Brian Eno on its instrumental, synthesised second side. After Bowie’s soundtrack to Roeg’s film had come to nothing, he sent the director a complimentary copy of his latest LP – complete with a cover created from an iconic still from his film of the flame-haired rock star in profile – with a simple note attached. “We all had pressures… deadlines,” recalled Roeg in 1993. “Eventually we brought in John Phillips to do the score. And then six months later David sent me a copy of Low with a note that said: ‘This is what I wanted to do for the soundtrack’. It would have been a wonderful score.”

But what exactly does this wonderful score sound like? Nicholas Pegg’s comprehensive book The Complete David Bowie offers this tantalising glimpse into what ought to have been: “The emerging soundtrack incorporated funk-styled instrumentals and slower, more ambient pieces, including a number called Wheels and an early version of what would become the Low track Subterraneans.” Bootlegs claiming to contain outtakes from the soundtrack are filed next to those containing recordings of The Beatles’ lost psychedelic masterpiece Carnival Of Light: unconvincing fakes. But outtake Some Are was a contender for a while at least. Mixed in 1991 and eventually released as a bonus track on a reissue of Low, this piece was alleged to have pre-dated Bowie’s 1977 set, actually written as part of the mythical lost soundtrack in 1975. Unfortunately for Bowie sleuths, the trail goes cold: its co-composer recalls the piece as “a quiet little piece Brian Eno and I wrote in the seventies”, retrospectively time-fixing it to Europe and not Los Angeles, where the aborted soundtrack sessions took place.

Recordings eventually began in late 1975 after the classic Station To Station album was in the can – a punishing work schedule for Bowie, considering he was simultaneously starring in a major motion picture, providing music for its soundtrack and cutting his next proper LP release. A mix of familiar and old faces were to form the musicians for the project: Space Oddity collaborator Paul Buckmaster was summoned to Cherokee Studios, contributing cello, among other instruments, along with Bowie’s rhythm section Carlos Alomar, Dennis Davis and George Murray. Again, according to Nicholas Pegg’s Bowie bible: “With Bowie’s guitar and Buckmaster’s cello accompanied by synthesisers and some of the earliest drum machines, the compositions were strongly influenced by Kraftwerk’s latest album Radio-Activity, released the previous month.”

Recordings eventually began in late 1975 after the classic Station To Station album was in the can – a punishing work schedule for Bowie, considering he was simultaneously starring in a major motion picture, providing music for its soundtrack and cutting his next proper LP release. A mix of familiar and old faces were to form the musicians for the project: Space Oddity collaborator Paul Buckmaster was summoned to Cherokee Studios, contributing cello, among other instruments, along with Bowie’s rhythm section Carlos Alomar, Dennis Davis and George Murray. Again, according to Nicholas Pegg’s Bowie bible: “With Bowie’s guitar and Buckmaster’s cello accompanied by synthesisers and some of the earliest drum machines, the compositions were strongly influenced by Kraftwerk’s latest album Radio-Activity, released the previous month.”

Buckmaster remembers proceedings less proto-Low than this account, however. According to David Buckley’s 2007 Mojo interview with him: “There were a couple of medium-tempo rock instrumental pieces, with simple motifs and riffy kind of grooves.” He confirms the presence of Bowie’s rhythm section, plus J Peter Robinson on Fender Rhodes, and himself on cello and overdubs using ARP Odyssey and Solina synthesisers. “There were some more slow and spacey cues with synth, Rhodes and cello,” Buckmaster added, “and a couple of weirder atonal cues using synths and percussion. There was also a piece I wrote and performed using some beautifully made African thumb pianos I had purchased earlier that year, plus cello, all done by multiple overdubbing.” He also confirms the presence of a Bowie vocal cut: “A song David wrote, played and sang, called Wheels… had a gentle sort of melancholy mood to it. The title referred to the alien train from his character Newton’s home world.”

The exact reason for the Holy Grail of the Bowie canon remaining in the vaults is still unclear. Bowie’s own recollection of the event was that he was so outraged that, when after finishing “five or six pieces”, he was told that he would be required to submit these compositions along with other people’s tracks, he withheld all of his contributions, choosing to pursue this instrumental vein to stunning effect with Brian Eno on Low. Can we really trust Bowie’s version of events, though? His drug-induced memory-wipe of most of that period is well-documented. Station To Station was recorded during the same time – a release about which “Bowie confesses that he was so addled he can hardly remember making the album”, according to writer Nicholas Pegg.

So, Buckmaster’s own view is more realistic, albeit a little negative perhaps. He believes the music wasn’t used for three reasons. From the aforementioned interview with Buckley: “Firstly, it was just not up to the standard of composing and performance needed for a good movie. Secondly, I don’t think it fitted well to the picture. And lastly, it wasn’t really what Nic Roeg was looking for.” He adds: “I considered the music to be demo-ish and not final, although we were supposed to be making it final. All we produced was something substandard, and Nic Roeg turned it down on those grounds…”

According to Bowie, “five or six” pieces in all were recorded, ultimately rejected by Roeg or abandoned by their composer. John Phillips, former leader of sixties hitmakers The Mamas & The Papas, was subsequently approached to pull the soundtrack together in London. He is one of the few people outside of the musicians involved to have heard the Bowie compositions, describing the material as “hauntingly beautiful, with chimes, Japanese bells, and what sounded like electronic wind and waves”, but his take on the project is a world away from impressionistic, Krautrock-influenced funk-rock, which these tantalising glimpses suggest the project could well have sounded like – a reasonable bet, considering the direction Bowie was to take in the late seventies and early eighties.

Philips presented the director with a mixture of his own bluegrass compositions, classical music, wistful ballads from the likes of Jim Reeves and The Kingston Trio, and contemporary pop and rock by Steely Dan and Joni Mitchell, among other predominantly American musical styles. All were a good fit for the arid landscape of New Mexico, where much of The Man Who Fell To Earth was being shot. Used in the film, Philips’ assemblage of everything from Louis Armstrong to his own country-rock twang is less a score, more a compilation of musical snippets, heard in fragments, tumbling from multiple radios, record players and futuristic hi-fi equipment. But facing a nightmare of negotiation with multiple labels and expensive clearances, the Philips version of the soundtrack to The Man Who Fell To Earth was also destined to remain, like the mythical Bowie score, in the vaults.

Despite having assembled a band featuring esteemed pedal steel player BJ Cole and ex-Rolling Stone Mick Taylor to assist with developing ideas for the soundtrack, perversely, Philips’ most outré selections are where the marriage of image and sound truly works. The film’s eerie, atmospheric instrumentals are courtesy of Japanese avant garde musician Stomu Yamash’ta – for example, an edit of his atmospheric Memory Of Hiroshima is used to brilliant effect at the start of the film, as Newton navigates his way into the remote town of his arrival on Earth. Five additional Yamash’ta selections are used in all: Poker Dice; 33 1/3; One Way; Mandala and the beautifully melancholy Wind Words. All are commercially available on official Yamash’ta releases.

Despite having assembled a band featuring esteemed pedal steel player BJ Cole and ex-Rolling Stone Mick Taylor to assist with developing ideas for the soundtrack, perversely, Philips’ most outré selections are where the marriage of image and sound truly works. The film’s eerie, atmospheric instrumentals are courtesy of Japanese avant garde musician Stomu Yamash’ta – for example, an edit of his atmospheric Memory Of Hiroshima is used to brilliant effect at the start of the film, as Newton navigates his way into the remote town of his arrival on Earth. Five additional Yamash’ta selections are used in all: Poker Dice; 33 1/3; One Way; Mandala and the beautifully melancholy Wind Words. All are commercially available on official Yamash’ta releases.

That elements of the Stomu Yamash’ta selections conjure up the ghost of seventies-vintage Pink Floyd is perhaps no coincidence. “In the first rough cut, I temp-scored the movie entirely with Pink Floyd music,” reveals the film’s editor Graeme Clifford in an interview for a documentary on the 2007 edition of the DVD release of the film. “The album [Dark Side] had only recently come out at that point [two years previously] and it was relatively new. It worked brilliantly. It complemented the picture enormously and gave it this enormous time spread… it felt like an eternity because of the style of the Pink Floyd music. Not surprisingly at that time, it was horrendously expensive to buy.”

The spacey vibe continues for sequences in which Newton’s thoughts drift back to his family on his dying home planet: for these scenes, special electronic and oceanic effects, including treated whale noises, were constructed by Desmond Briscoe, pioneer of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution to suitably otherworldly effect. We fall back to earth, however, for the final frames, credits rolling over the slumped figure of the terminally inebriated Newton, now a permanent resident of terra firma, his mission to save his homeworld long abandoned, as Artie Shaw’s Stardust – Roeg’s nod to Ziggy, perhaps? – plays us out as the theatre lights go up…

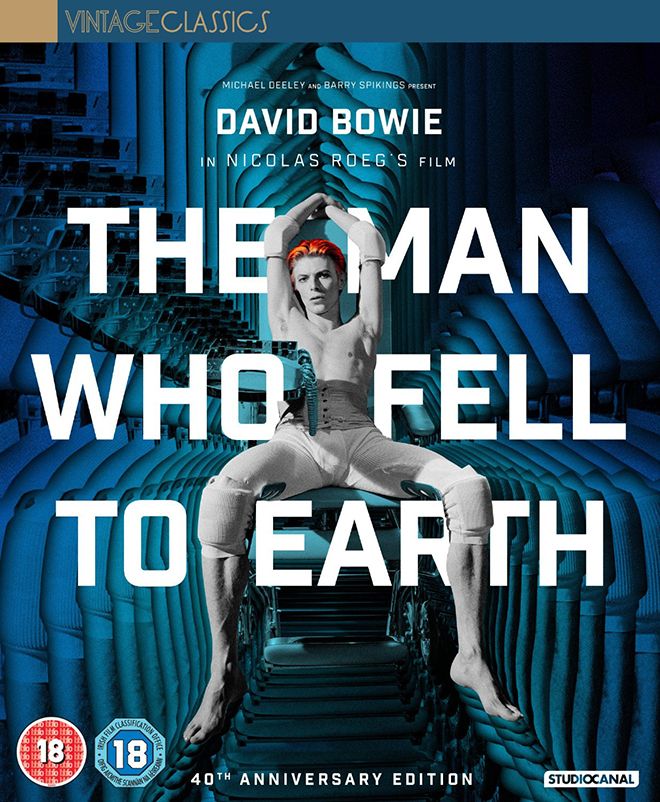

Some 40 years after the release of Roeg’s masterpiece, enterprising souls have attempted to piece together Philips’ soundtrack in various forms, taking the end credits as their source of musical information and disseminating their findings via YouTube playlists (since pulled) and less-than-legal filesharing sites. With a Spotify account, you can even have an attempt at constructing an (incomplete) playlist yourself. And the good news is that a John Philips CD is being bundled with the 40th anniversary edition of the movie on Blu-ray.

But what about Bowie’s mythical score? It’s obvious that he had great affection for the film, choosing iconic images from it to adorn the sleeves of two of his greatest seventies albums – Station To Station and Low – so perhaps in the inevitable emptying of the Bowie vaults in the years after his death, we can but hope that an archivist will eventually wipe the dust off the mastertapes marked The Man Who Fell To Earth and finally ready them for eager public consumption.

Perhaps it’s perversely appropriate that both versions of the soundtrack remain unreleased. In an attempt to send messages from Earth to his wife and family on his dying planet, Bowie’s character records an album, the contents of which will be sent into the cosmos as radio waves. As Chris O’Leary elegantly puts it in his book Rebel Rebel: All The Songs Of David Bowie From ’64 To ‘76: “It’s fitting that Thomas Jerome Newton records an album in the film (released by ‘The Visitor’) whose music we never hear. The Man Who Fell To Earth is Bowie’s anti-Elvis movie, a film whose rock star lead doesn’t sing a note.”

Following the publication of this feature in the August issue of HFC, UMC has announced that it will be releasing for the first time in any format the original movie soundtrack containing works by Stomu Yamash'ta and John Phillips. You can find out more here.

|

Inside this month's issue: Neat Acoustic Mystique Classic floor standing loudspeaker, Austrian Audio The Composer headphone, T+A PSD 3100HV network-attached DAC/preamp, Audio-Technica AT-SB727 Soundburger portable turntable, a preamplifier Group Test and much, much more...

|